Pt 2: foodways, Watery Abundance: Building Collective Action Through Food Landscapes

In the northern territories, food accessibility is not a problem that can be solely solved by engineers or the construction of a new grocery store. Climate change itself increases the risk of fresh food insecurity among Indigenous communities across the Arctic, and exacerbates the loss of permafrost and lichen, a main food source for Caribou populations. Indigenous tribes such as the Gwich’in have a commensalistic relationship with Caribou populations, whose herd size and location depend on the fragile ecosystem of the evanescent Arctic and are critical to the preservation of the permafrost. Climate change is repeatedly demonstrated to be impacting on the ecosystems supporting both humans and non-human communities.

“Culturally, foodways are networks. Caribou, berries, and fish entangle intergenerational Indigenous women; their pathways are vast and interconnected, forming expansive territories of land and water stewardship. ”

Culturally, foodways are networks. Caribou, berries, and fish entangle intergenerational Indigenous women; their pathways are vast and interconnected, forming expansive territories of land and water stewardship. For instance, berry picking and fish camps along the Mackenzie River are critical to the wellbeing and sharing rituals of Gwich’in communities. Agency in communities is not given [by designers], but is embodied in land and in everyday living between both humans and the nonhuman. Canadian national policy, however, is currently ignorant of this fact. Throwing money every year to subsidize grocery items such as imported kiwis from Australia, these national subsidies are band-aids on a spiraling situation, holding on to an idealized notion of embedding the arctic into the logic of modern capital-product flows. Kiwis from across the planet are being subsidized, while local foodways such as nutrient-rich lichen and generations of local caribou herds are subsequently erased. In the words of Silvia Federici, “by undermining the self sufficiency of the region and creating total economic interdependence, globalization generates not only recurrent food crises but a need for an unlimited exploitation of labor and the natural environment.”

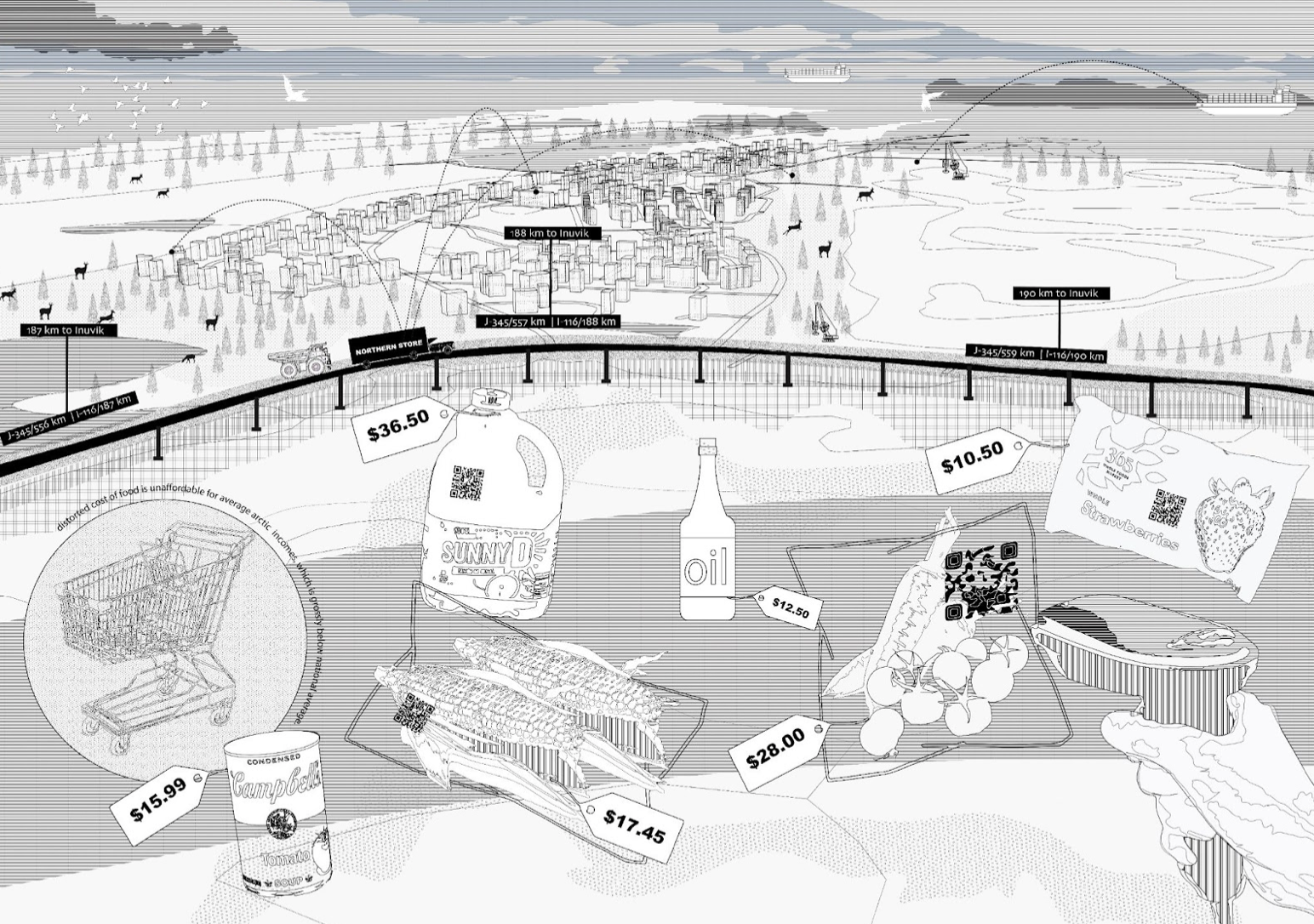

These policies are an active and conscious act of modern day genocide to force out traditional foodways, to replace indigenous abundance with foreign-imposed scarcity. $35 for a bottle of industrial orange juice, $28 for a bag of grapes, and $105 for a pack of mineral water is heavily disproportionate to average incomes, which is grossly below national average. As the Gwich’in chef Richie Francis aptly wrote, “if you control the food, you control the people''. A few months ago, an article titled “The Many Faces of Indigenous Culture and Food” was published. Jennifer Brandt builds upon Richie Francis’s comment, saying that “the attempted eradication of [their] culture has been as horrific as the eradication of [their] people...reclaiming traditional foodways is radically political”. In Of Morsels and Marvels, the author Maryse Condé writes that “a country’s cuisine mirrors the character of its inhabitants and transfigures the imagination. Visiting a supermarket is as instructive as going to a museum or an exhibition.” Here, to replace ‘supermarket’ with ‘Landscape’, perhaps rethinking food making as process, materiality, and as rituals embedded in landscape is an initial step towards decolonizing foodways.

“Rethinking food making as process, materiality, and as rituals embedded in landscape is an initial step towards decolonizing foodways.”

The subtext of the role of a designer in places with extreme climates or conditions is vague. In Design School, we are educated to navigate zoning codes within urban governance, to build tactical structures for a paying public (pacification by cappuccino is what Sarah Zukin calls it), to 3D model varieties of balconies and rooftops. But we are ill prepared to design in extreme climate conditions. What would it even mean to be a designer for the arctic? Do they even need us, me, or you there? There are already, after all, numerous Gwich’in designers for millenia, building from scratch the resilient structures that invite cold flows of strong winds and the migratory turn and bends of the Peel River. In thinking about food security in the arctic, we have been reflecting on our purpose here and what it is we can offer as an outsider-person. Instead of designing hydroponic growing structures or greenhouses to grow food, it is more critical to look back to the landscape itself and its variety of richness and existing abundance.

Preserve vs. Reclaim

One keyword/term constantly resurfacing while working on cultural preservation of food rituals in the Northwest Territories was the word ‘preservation’ itself. Tracing the word ‘preserve’, it became widely used in the 1950s by environmentalists in the context of environmental conservation and protection against pollution. The idea that to preserve something there is a protagonist and an antagonist, someone or something to insulate and shelter from. Protecting things against weathering, protecting things from spoiling or going ‘bad’. Protecting things from oxidizing (breathing?) Thinking about the preservative itself as a liquid. Chemicals. Unnatural. Frozen against time. Unchanging. Thinking about foods that are preserved (literally). Pickles? Dried things.

Preservation is a fraught territory with a long violent history of erasure and sealing up into institutions for display to a foreign public. In this sense, perhaps the term reclaim is more apt. Unlike preserve, which is static and freezing in time, reclaim sounds more active, a verb. Something that is in process, prompting questions like what it means to have a sense of ownership over one’s own culture, a retrieval of identity lost, an actioning emerging from oneself rather than as the result of another's imposing over.

Culture, in all its earlier uses, was a noun of process: the tending of something. To inhabit, cultivate, protect, honor with worship. A culture or commons of care, perhaps what Silvia Federici calls communities of resistance that oppose social hierarchies in Re-Enchanting the World. To my knowledge, this notion of care and honor is actively practiced among Gwich’in elders. The teet’lit Gwich’in term ‘gwiinzii kwundei’ refers to the Good Life, of being out on the land as a pivotal source of well being and healing. Three actionings that are, following Gwich’in education, crucial in living the life, and form integral practices in being: visiting and sitting with, doing things and working with, and taking care of things.