Architecture and Aetiology:

Ramblings on practice and climate nihilism

by Thomas Hyo-min King

Thomas Hyo-min King is a dual Master of Architecture and Master of City Planning candidate whose work explores the role of architecture in our shifting energy regime, examining how the political ecology of building production, technology, and practice can reinforce or challenge meaningful climate action. He holds a Bachelor of Science in Architecture from McGill University, where he serves as a research lead at Reconstruct, an R&D initiative developing a mass deep-energy retrofit program for Quebec. Previously, he worked as an urban designer on projects addressing urban health, coastal vulnerability, and water scarcity across Asia and the Middle East, and co-founded Biocene, a cleantech startup focused on water remediation and waste upcycling. His research has been published in Buildings & Cities, the Passive House Institute of the US, Cellar Architectural Journal, and the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture.

The workshop investigated material cultures of forestry in the Finnish Lakeland. Combining theoretical explorations and ‘timber cruises’—forest excursions to document and represent tree stands—the course provided participants with an opportunity to interrogate timber provenance and its attendant value systems, instruments, and technologies. Pictured here: a timber cruise diagram on the workshop poster.

This reflection stems from my own experience designing and conducting a two-week workshop, in collaboration with Robbe Pacquée, in Savonlinna, Finland, from July 27 to August 10, 2025. The workshop, entitled “Timber Cruising in the Chthulucene,” was taught as part of the 45th European Architecture Students Assembly (EASA) under the theme ‘rhizome,’ which solicited proposals that aim to interrogate the responsibilities and accountabilities of architectural practice and pedagogy within broader arrays of ecology and power.

In an unabashed, 256-page critique on new materialism and human agency in the age of climate breakdown, Andreas Malm’s The Progress of This Storm cautions that recent turns in the environmental humanities have made it difficult to discern the causes and effects of anthropogenic climate change. To elaborate: efforts to dismantle the stronghold of Cartesian thinking—which has cemented a binary worldview where humans and society exist apart from the forces of nature—has solicited calls to upend anthropocentric superiority by effacing the distinction between humans and nature entirely. Nature has been re-vested with the power of agency, and humans are but one among a constellation of actants that make and remake each other in frictional, and at times, harmonious, transactions. But while the proponents of new materialism have done significant theoretical work in creating room for less dualist, relational ways of thinking (that have become so fashionable in architectural praxis), Malm posits that extremism begets extremism: a crisis of theory has emerged that has non-negligible and possibly dire consequences. The complete dissolution of specifically human agency, where all living and non-living matter is equally agentic, releases social actors from causal accountability for the impacts of (uneven) human activity on the planet. The question Malm poses at the scale of political ecology reverberates deeply within architectural discourse and practice: where do architecture’s responsibilities lie in the environmental crisis and what power do we have to change course?

Within such a paradigm of contradiction, existentialism abounds. The increasing transparency of architecture’s implications in far-flung circuits of extraction and expropriation force a reckoning of agency among practitioners, academics, and students alike. Its effects are particularly pronounced in the space of pedagogy, where for some, the crisis manifests as a sort of paralysing nihilism; the contingencies of architectural production in a world order of systemic harm means any intervention is necessarily malign and futile, leaving room for no intervention at all. For others, climate nihilism facilitates disregard for the political implications of building, serving as justification for a depoliticized practice. In this camp, an aesthetic practice devoid of meaning is the primary domain of the architect—in other words, the command of formal and material operations to bring sensible value to space, where ‘values’ in this instance have no intentional engagement with the politicized nature of architectural production—effectively relinquishing practitioners from liability to larger social and environmental outcomes. Architects need not imbue design with purpose in the name of climate (or other) concerns, because it is simply not within the bounding box of the discipline to do so. Climate nihilism as an architectural praxis thus remains normatively apolitical: the question of whether architecture should (or can) contribute to a larger climate mission is not on the table.

While nihilism practices architecture as a primarily formal project, a similarly formal but radically different position provides a counter. Instead, the aesthetic arena of architecture is understood to be the most politically operative. Here, there is a necessary cognizance of building production as an outcome of upstream power relations (that render architectural interventions subject to ulterior agendas), but as opposed to nihilism, design in this camp occupies a more altruist tone. Formal and material operations are conducted in a sort of trickle-down/up aspiration: an attention to beauty curries social value, and therefore cultures of care. Aesthetics generate an alternative politics that has causal effects on what we might analogously call the “linkages” of architecture—or what Albert Hirschman investigates as “micro-Marxism”—that is, the micro-structural social and material relations preceding and succeeding the production of buildings. Aetiologically speaking, aesthetics are wielded to cultivate divergent value systems, spatial behaviours, and material awarenesses that induce a chain reaction in the linkages of the built environment. An obvious historical example is delineated in Bernadette Bensaude-Vincent’s exposé Accumulation: The Material Politics of Plastic, where a material that, prior to the 1960s, was the “hallmark of cheap substitutes,” quickly garnered aesthetic currency through its deployment by designers in high-end, luxury goods and homes. Architects played a central role in transforming the plastic value system, which had manifold effects across commodity chains, the environment, and the place of plastic in the social imaginary. A similar practice can be seen today, as architecture has now (ironically) taken it upon itself to undo the plastic deepening it helped sow, by promoting an aesthetic turn toward biogenic materials, wood products, and other non-petroleum-based assemblies.

The course asked students to examine how ideologies of human exceptionalism, growth, efficiency, utility-based value, and technical rationalization are perpetuated by established standards and processes for material extraction, particularly in the realm of forestry, and consequently, how such regimes of knowledge have designed how we relate to material resources and the biosphere. Pictured here: students conducting a timber cruise to survey and take stock of a tree stand.

In some ways, redefining the scope of architectural projects to interrogate or intervene in broader politico-economic arenas feels like a disciplinary overstep—but the nature and immediacy of climate change perhaps urges us to revisit this sentiment. Sensibly so, as architecture has, according to some scholars, inherited a centuries-old epistemic tradition of Western science that was arranged both intellectually and institutionally around “disciplines,” in which specialists were trained to amass a high level of expertise in a narrowly bounded area of inquiry. As Naomi Oreskes and Erik Conway elaborate in their essay on the history of climate change, The Collapse of Western Civilization, this “reductionist” approach was thought to provide intellectual power and rigour to research by focusing on discrete, tractable elements of larger complex problems. While reductionism and tractability helped advance many domains, they inhibited correlative investigations of complex phenomena—effectively rendering it difficult for scientists to both articulate and/or feel empowered to speak to the causes and effects of climate change. Today, that legacy persists in many architectural institutions and their curricular mandates. It follows that the tension that emerges at the interface of reductionist expertise, nihilism, and complex socioecological problems is what provokes, in part, an existentialism of agency within the discipline.

Against the backdrop of these structural and epistemic constraints, Malm’s call to dialectical materialism offers one part of a framework that might help architectural practice gain common political ground. Here, agency is neither an ontological property equally distributed across all beings nor a transcendent human privilege, but a historically situated capacity for understanding the effects of social action on material phenomena. Society possesses a unique set of emergent properties (not latent to nature) that can be reconfigured as much as they were intentionally constructed. This is not to deny the potency of other nonhuman forces, but to assert that agency is asymmetrical and operates through social chains of causation—whether these are supply chains and material standards, procurement policies and regulatory frameworks, or business models, maintenance regimes, and labour and construction practices. Understanding architecture’s aetiology through this web then helps identify moments of rupture that may renegotiate the engagements of building production in broader environmental outcomes.

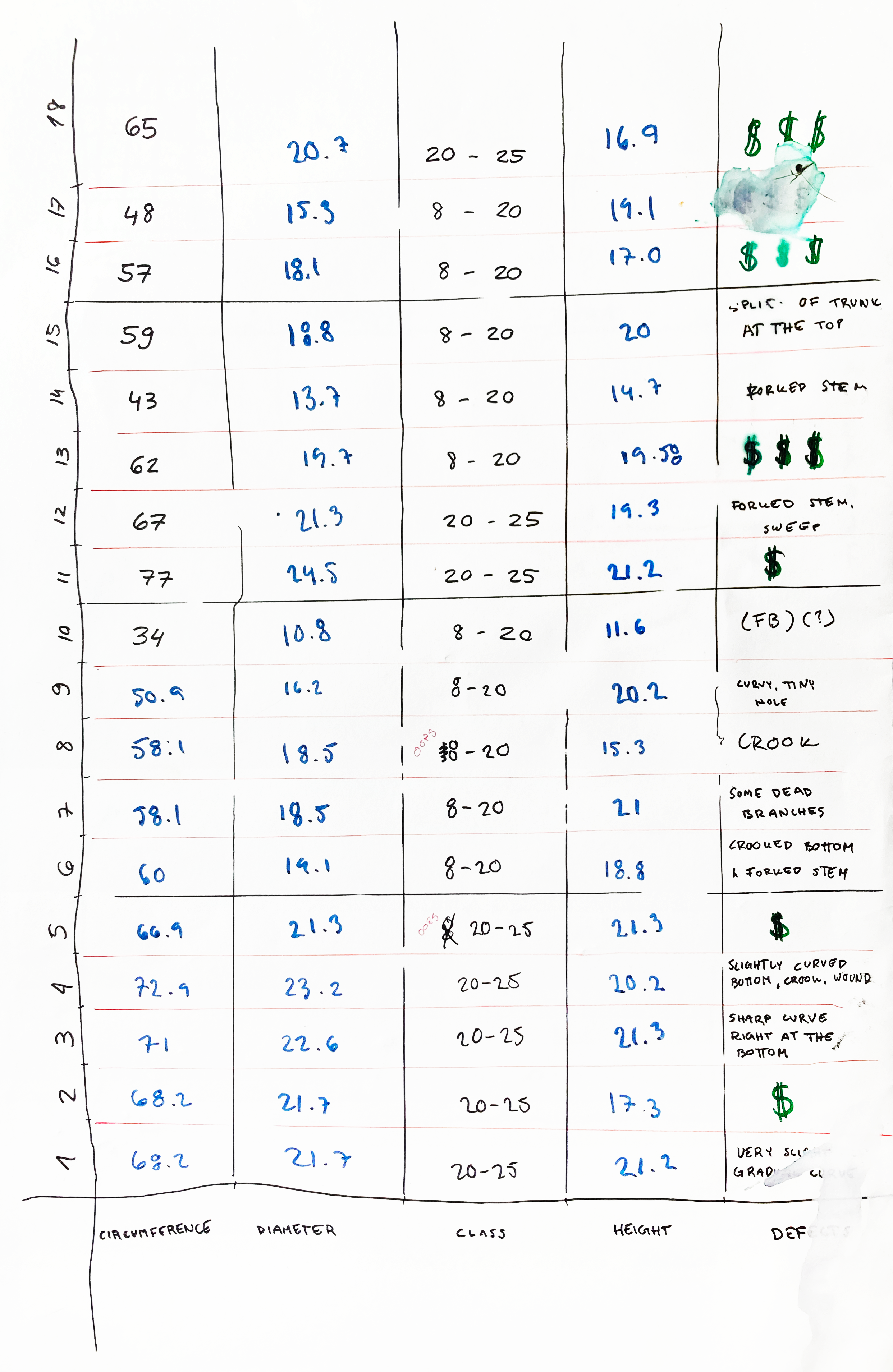

Mainstream architectural discourse has placed a large emphasis on the afterlife of materials or their byproducts—as ejected from industrial processes and at the time of extraction—rather than on upstream logics of resource appraisal, selection, and harvesting that constitute timber waste streams. Conventional timber cruises reduce forests to a limited array of structural and ecological traits that is often oriented towards determining the total merchantable volume of lumber of a given tree stand for capital accumulation. Pictured here: a sample of the tree stock evaluated by students during a preliminary timber cruise.

For the final project, students were asked to conduct their own version of a timber cruise: in this instance, a forest excursion geared towards surveying and representing a given tree stand with the intent of communicating and advocating for an alternative forest value. The goal was to explore and expand upon an area of interest in relation to the forest and one’s positionality to it, and launch an inquiry of fieldwork and representation that subverts extractivist timber sourcing practices.

Admittedly, this incrementalist approach feels in some ways closest to what might be a realist definition of agency for the discipline of architecture: meaning a praxis based in cumulative action and an acceptance of the constraints of existing economic and political systems. However, a submission to realism leaves practice susceptible to the forces that choreograph it, and increasingly diminishes the agency of architects—who have fewer and fewer linkages through which to effect meaningful change—at least within a speculative market economy that construes buildings primarily as financial instruments. The incrementalist position, although benevolent, is not equipped with tools to resist the contraction of the architectural arena and urgently confront the multiple compounding crises that climate change renders legible in the built environment. How, then, can architecture pursue structural climate action? Does our current existential paradigm demand a redefinition of agency within the practice of architecture?

It might be worth investigating the aetiology of architecture: that is, the causal phenomena underlying the problems practitioners inherit in the process of building design and construction. Rather than assume a passive, reactionary position to such effects, the age of climate change might necessitate more proactive, and transdisciplinary, forms of intervention that, at the very least, reckon with problems at their root. Indeed, an incrementalist practice that does not negotiate with structural linkages further upstream or downstream of building production can, in cases, exacerbate greater harm. This is among the most alarming risks of the contemporary frontier of architectural pedagogy and research, where much emphasis has been placed on the capacity for architects to simply address the symptoms (rather than manners of causation) of uneven and injurious urban metabolism, with projects of efficiency, reuse, and optimization. There is a pedagogical reluctance here to confront Jevon’s Paradox, which tells us that increased efficiencies can lead to deeper cycles of consumption and self-destructing growth, by decreasing costs and ultimately increasing global material and energetic throughput. Evidently, the paradox is not in the foreground of academia or practice, as recent fashions for reuse, retrofit, remediation, and all manners of re- without structural reckoning can reduce architectural interventions to techno-fixes in the face of climate breakdown. While these projects are critical and urgent, they risk remaining a band-aid on a much larger operation of extraction, and co-option to frontiers for capitalist accumulation in and of themselves.

The task of the final timber cruise was to identify a value latent to the forest while taking stock of tangible and/or intangible forest properties that together formulate a system of measure for the value in question. Having identified a forest value and appropriate system of metrics, students were asked to determine a medium of representation capable of communicating the value and advocating for its significance. In the spirit of cruising, the objective was to transform the knowledge systematically to produce a syntax that is legible and reproducible in future cruises. Pictured here: the cover page of a final timber cruise conducted by workshop participants Julia Finch and Sunna Wedel. The intention was to uncover nocturnal woodland traits in relation to darkness-inspired Nordic mythologies to contest the diurnal visual regime of conventional timber cruising methods.

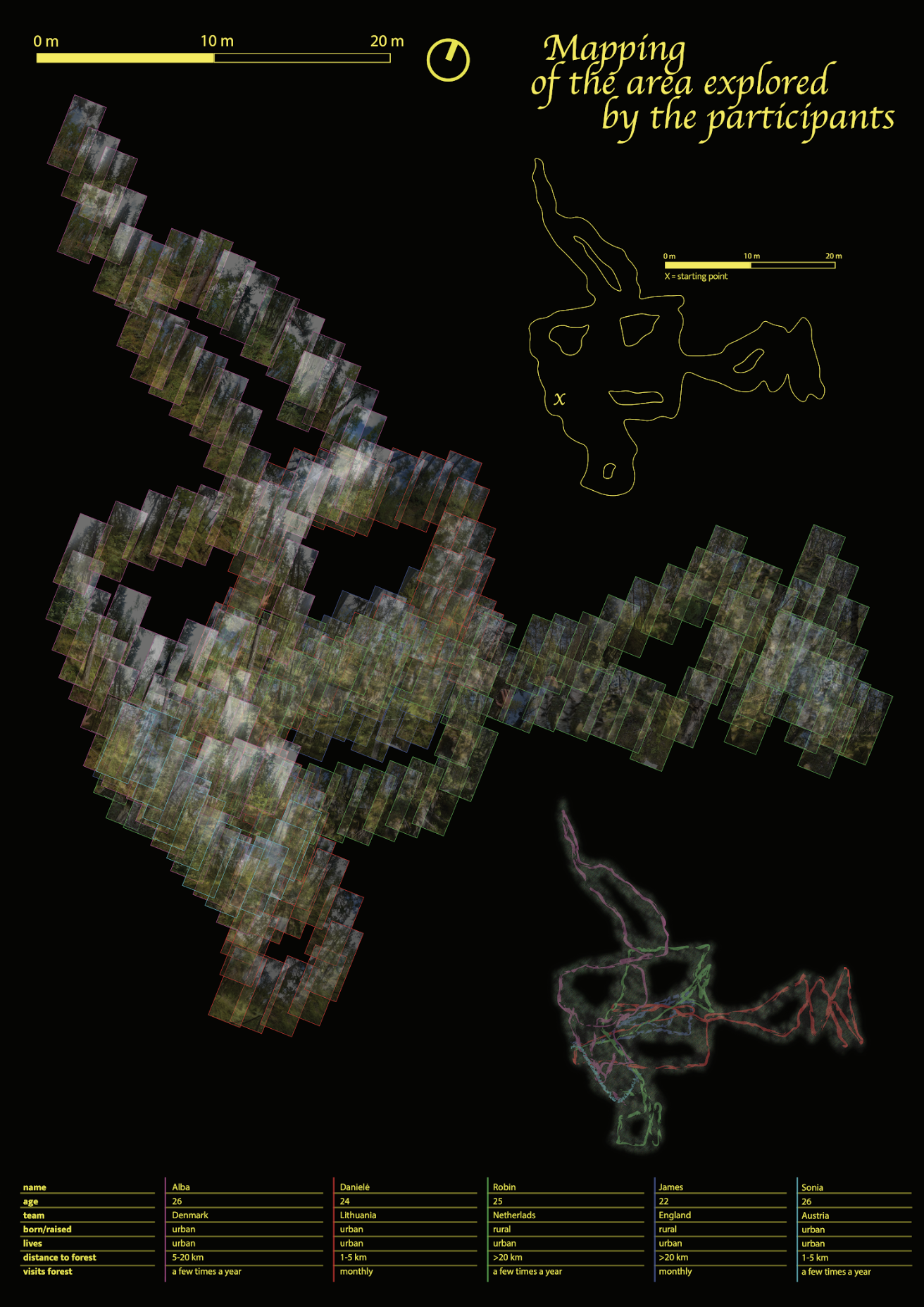

Pictured here: a final timber cruise conducted by workshop attendees Villads van Toorn Brix, Vivien Werner, and Vėjas Stalgys, who studied the democratic production of value in the forest by inviting various participants to carry out a timber cruise collectively. The project sought to identify correlations between forest navigability, sensible value, and spatial cognition by prompting participants to wander the tree stand based on each individual’s politics and perception of aesthetics.

While this is less a call to overhaul all contracts of architectural conduct, it is an appeal to engage meaningfully with the causal relations and value systems that underwrite architectural production. If architects are to play their part in the age of climate breakdown, they must reckon with the limitations of nihilism or reductionism, moving beyond building production as a reactive instrument of capital or a vessel for climate-averse political agendas. Rather, it means cultivating a design praxis that is necessarily political, transdisciplinary, and proactive, to understand architecture as an arena for arbitrating the forces that produce it. To redefine agency, then, is not to dissolve it into the flux of matter, nor to retreat into non-action, but to work through building as a platform for urgent mediation: one capable of discerning where and how to intervene in the tangled aetiologies of the environmental crisis.

Students presenting their final timber cruising projects on the last day of the workshop at the edge of the forest. Workshop participants: Daniel Andrèe Martínez Juárez, Giedrė Jurkuvėnaitė, Živa Potnik, Maja Perpar, Rodrigo Godoy González, Tsovinar Khalatyan, Villads van Toorn Brix, Vivien Werner, Vėjas Stalgys, Diana Tumėnaitė, Mustafa Çağlak, Saalim Elhaj, Julia Laura Finch, and Sunna Wedel.